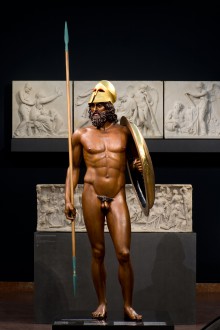

In addition to the Corinthian helmet, the missing elements included the shield and spear. To prepare for the reconstruction of the latter two objects, we worked in the storerooms of the Archaeological Museum of Olympia during the summer of 2014. During the excavations carried out by German archaeologists from 1876 onward, many weapons were found that had been consecrated by believers in the sanctuary of Zeus. These included spearheads, spear butts, metal shield coverings and a variety of decorative elements. Our photographic documentation of these items provided the basis for our work on the missing parts.

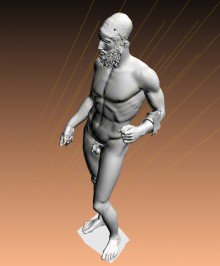

However, it was clear to us from the outset that we must take as our model not a “real” shield but one that was a product of Greek sculpture, that is to say an artist’s version of a shield. In late 2014 we therefore arranged to meet with our colleagues and a small scanning team in front of the famous East Pediment of the Temple of Aphaia in the Glyptothek in Munich. There the dying Trojan king is shown supporting himself on his marble shield, which has survived in near entirety. The scanned data had to be cleansed using a complex process. Before the moulds could be produced by means of a 3D printer, there were many points to be considered in consultation with the bronze casters. As the shield was to be made by hollow casting, four partial moulds with internal supporting ribs were defined. The supporting ribs were necessary to prevent the moulds from moving in relation to one another even by a few tenths of a millimetre.

In close collaboration with Frankfurt goldsmith Kristina Balzer, gemstone polishers from Idar-Oberstein fashioned eyes for the bronze reconstruction of the statue. The white of the eye is made of quartzite, the iris of citrine, the ring around the iris of caramelized agate, the pupil of obsidian and the caruncle of pink coral. What makes the result so convincing is the perfect polish of the stones, which effectively reproduces the liquid quality of the human eye.

At first we feared we would be unable to replace the spear missing from the warrior’s right hand, because in the entire domain of Greek sculpture not a single spear has come down to us. Although we knew what a “real” spear butt and a “real” spearhead from the period of the Riace bronzes – that is, around 440 BC—looked like, we had no way of knowing how these elements had been reproduced and formally interpreted by the artist, not to mention the exact dimensions of a spearhead or the precise shape of the shaft. By a stroke of luck, all of these problems were suddenly resolved. It just so happened that, in the autumn of 2014, in the course of Greek underwater excavations off the island of Antikythera, a complete bronze spear from a lost Greek sculpture was discovered and we were able to use this as our model.